"Almost everyone said they ate more."

I read this article today in the NY Times. It really affected me, especially the last sentence in it. I feel really sad how food is becoming the enemy of so many people nowadays; we have a love/hate relationship with food; an unhealthy link. We are so afraid of being fat and being a part of a statistic, that we eat more, to counteract feeling bad about how we look.

Was it always like this? I imagine it has been around longer than we think, but I had blind eyes to it because I was far from being considered a plump person. Now I am a plump person, and I feel like I almost in denial about it because I haven't changed my habits that much. I suffer from this intense vanity that doesn't allow me to ignore the beautiful people around me; I want to be one of those skinny bitches on the subway, the ones that make jeans look good. Not anything like me.

I know that my relationship with food is not entirely unhealthy. I am aware of what I eat and do a good job of not going overboard. So this post is not a cry for help, I promise. I guess what I have been reading and hearing around me has affected me. It pains me to see people almost hating themselves for loving food. Food is the best thing in the world, I think. It could be anything you want it to be, mean anything you want to mean. When people take a bite to eat, and all they see is their reflection in a mirror, where is the joy and the happiness?

I don't know what the answer is for people around the world to get over this epidemic. Maybe, in my lifetime, I'll never know. Just wanted to share this article, because at the moment, I have more than enough time on my hands, and thankfully, I am using that time to read and not pig out!

October 29, 2006

For a World of Woes, We Blame Cookie Monsters

By GINA KOLATA

FIRST we said they were ruining their health with their bad habit, and they should just quit.

Then we said they were repulsive and we didn’t want to be around them. Then we said they were costing us loads of money — maybe they should pay extra taxes. Other Americans, after all, do not share their dissolute ways.

Cigarette smokers? No, the obese.

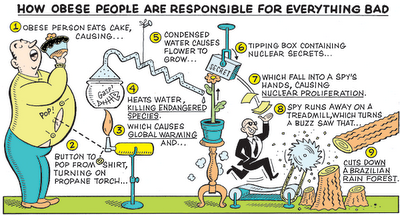

Last week the list of ills attributable to obesity grew: fat people cause global warming.

This latest contribution to the obesity debate comes in an article by Sheldon H. Jacobson of the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana and his doctoral student, Laura McLay. Their paper, published in the current issue of The Engineering Economist, calculates how much extra gasoline is used to transport Americans now that they have grown fatter. The answer, they said, is a billion gallons a year.

Their conclusion is in the same vein as a letter published last year in The American Journal of Public Health. Its authors, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, did a sort of back-of-the-envelope calculation of how much extra fuel airlines spend hauling around fatter Americans. The answer, they wrote, based on the extra 10 pounds the average American gained in the 1990’s, is 350 million gallons, which means an extra 3.8 million tons of carbon dioxide.

“People are out scouring the landscape for things that make obese people look bad,” said Kelly Brownell, director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale.

And is that a bad thing? Dr. Jacobson doesn’t think so. “We felt that beyond public health, being overweight has many other socioeconomic implications,” he said, which was why he was drawn to calculating the gasoline costs of added weight.

The idea of using economic incentives to help people shed pounds comes up in the periodic calls for taxes on junk food. Martin B. Schmidt, an economist at the College of William and Mary, suggests a tax on food bought at drive-through windows. Describing his theory in a recent Op-Ed article in The New York Times, Dr. Schmidt said people would expend more calories if they had to get out of their cars to pick up their food.

“We tax cigarettes in part because of their health cost,” he wrote. “Similarly, the individual’s decision to lead a sedentary lifestyle will end up costing taxpayers.”

Eric Oliver, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, said his first instinct was to laugh at the gas and drive-through arguments. But such claims often get wide attention, he says, and take on a life of their own.

“This is like, let’s find another reason to scapegoat fat people,” Dr. Oliver says.

At an annual meeting of the Obesity Society, one talk correlated obesity with deaths in car accidents, and another correlated obesity with suicides. Dr. Oliver, who attended, said no one in the crowd of at least 200 questioned whether the correlations were really cause and effect. “The funny thing was that everyone took it seriously,” he said.

Katherine Flegal of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also wryly cautions against being quick to link cause and effect. “Yes, obesity is to blame for all the evils of modern life, except somehow, weirdly, it is not killing people enough,” she said. “In fact that’s why there are all these fat people around. They just won’t die.”

The message in the blame-obesity approach, said James Marone, a political science professor at Brown University, is that it is so important to persuade fat people to lose weight that common sense disappears.

“Anything we can say to persuade you, we will say,” Dr. Marone added.

So is it working?

It doesn’t seem to be. Fat people are more reviled than ever, researchers find, even as more people become fat. When smokers and heavy drinkers turned pariah, rates of smoking and drinking went down. Won’t fat people, in time, follow suit?

Research suggests that the stigma of being fat leads to more eating, not less. And if reducing the stigma suggests a solution, that’s not working either.

“One hypothesis about getting rid of stigma is having more contact with the stigmatized group,” Dr. Brownell says. But with obesity, the stigma seems to be growing along with the national girth.

He cites a famous study in the 1960’s in which children were shown drawings of children with and without disabilities, as well as a drawing of a fat child. Who, they were asked, would you want for your friend? The fat child was picked last.

Now, three researchers have repeated the study, this time with college students. Once again, almost no one, not even fat people, liked the fat person. “Obesity was highly stigmatized,” wrote the researchers, Janet D. Latner of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, Albert J. Stunkard of the University of Pennsylvania and C. Terence Wilson of Rutgers University, in the July 2005 issue of Obesity Research.

One problem with blaming people for being fat, obesity researchers say, is that getting thin is not like quitting smoking. People struggle to stop smoking, but many, in the end, succeed. Obesity is different. It’s not that the obese don’t care. Instead, as science has shown over and over, they have limited personal control over their weight. Genes play a significant role, the science says.

That is not a popular message, Dr. Brownell says. And the notion that anyone can be thin with a little effort has consequences. “Once weight is due to a personal failing, a lot of things follow,” he said. There’s the attitude that if you are fat, you deserve to be stigmatized. Maybe it will motivate you to lose weight. The opposite happens.

In a paper published Oct. 10 in Obesity, Dr. Brownell and his colleagues studied more than 3,000 fat people, asking them about their experiences of stigmatization and discrimination and how they responded.

Almost everyone said they ate more.

For a World of Woes, We Blame Cookie Monsters

By GINA KOLATA

FIRST we said they were ruining their health with their bad habit, and they should just quit.

Then we said they were repulsive and we didn’t want to be around them. Then we said they were costing us loads of money — maybe they should pay extra taxes. Other Americans, after all, do not share their dissolute ways.

Cigarette smokers? No, the obese.

Last week the list of ills attributable to obesity grew: fat people cause global warming.

This latest contribution to the obesity debate comes in an article by Sheldon H. Jacobson of the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana and his doctoral student, Laura McLay. Their paper, published in the current issue of The Engineering Economist, calculates how much extra gasoline is used to transport Americans now that they have grown fatter. The answer, they said, is a billion gallons a year.

Their conclusion is in the same vein as a letter published last year in The American Journal of Public Health. Its authors, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, did a sort of back-of-the-envelope calculation of how much extra fuel airlines spend hauling around fatter Americans. The answer, they wrote, based on the extra 10 pounds the average American gained in the 1990’s, is 350 million gallons, which means an extra 3.8 million tons of carbon dioxide.

“People are out scouring the landscape for things that make obese people look bad,” said Kelly Brownell, director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at Yale.

And is that a bad thing? Dr. Jacobson doesn’t think so. “We felt that beyond public health, being overweight has many other socioeconomic implications,” he said, which was why he was drawn to calculating the gasoline costs of added weight.

The idea of using economic incentives to help people shed pounds comes up in the periodic calls for taxes on junk food. Martin B. Schmidt, an economist at the College of William and Mary, suggests a tax on food bought at drive-through windows. Describing his theory in a recent Op-Ed article in The New York Times, Dr. Schmidt said people would expend more calories if they had to get out of their cars to pick up their food.

“We tax cigarettes in part because of their health cost,” he wrote. “Similarly, the individual’s decision to lead a sedentary lifestyle will end up costing taxpayers.”

Eric Oliver, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, said his first instinct was to laugh at the gas and drive-through arguments. But such claims often get wide attention, he says, and take on a life of their own.

“This is like, let’s find another reason to scapegoat fat people,” Dr. Oliver says.

At an annual meeting of the Obesity Society, one talk correlated obesity with deaths in car accidents, and another correlated obesity with suicides. Dr. Oliver, who attended, said no one in the crowd of at least 200 questioned whether the correlations were really cause and effect. “The funny thing was that everyone took it seriously,” he said.

Katherine Flegal of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also wryly cautions against being quick to link cause and effect. “Yes, obesity is to blame for all the evils of modern life, except somehow, weirdly, it is not killing people enough,” she said. “In fact that’s why there are all these fat people around. They just won’t die.”

The message in the blame-obesity approach, said James Marone, a political science professor at Brown University, is that it is so important to persuade fat people to lose weight that common sense disappears.

“Anything we can say to persuade you, we will say,” Dr. Marone added.

So is it working?

It doesn’t seem to be. Fat people are more reviled than ever, researchers find, even as more people become fat. When smokers and heavy drinkers turned pariah, rates of smoking and drinking went down. Won’t fat people, in time, follow suit?

Research suggests that the stigma of being fat leads to more eating, not less. And if reducing the stigma suggests a solution, that’s not working either.

“One hypothesis about getting rid of stigma is having more contact with the stigmatized group,” Dr. Brownell says. But with obesity, the stigma seems to be growing along with the national girth.

He cites a famous study in the 1960’s in which children were shown drawings of children with and without disabilities, as well as a drawing of a fat child. Who, they were asked, would you want for your friend? The fat child was picked last.

Now, three researchers have repeated the study, this time with college students. Once again, almost no one, not even fat people, liked the fat person. “Obesity was highly stigmatized,” wrote the researchers, Janet D. Latner of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, Albert J. Stunkard of the University of Pennsylvania and C. Terence Wilson of Rutgers University, in the July 2005 issue of Obesity Research.

One problem with blaming people for being fat, obesity researchers say, is that getting thin is not like quitting smoking. People struggle to stop smoking, but many, in the end, succeed. Obesity is different. It’s not that the obese don’t care. Instead, as science has shown over and over, they have limited personal control over their weight. Genes play a significant role, the science says.

That is not a popular message, Dr. Brownell says. And the notion that anyone can be thin with a little effort has consequences. “Once weight is due to a personal failing, a lot of things follow,” he said. There’s the attitude that if you are fat, you deserve to be stigmatized. Maybe it will motivate you to lose weight. The opposite happens.

In a paper published Oct. 10 in Obesity, Dr. Brownell and his colleagues studied more than 3,000 fat people, asking them about their experiences of stigmatization and discrimination and how they responded.

Almost everyone said they ate more.

1 comment:

Hi Ilana,

I know how you feel on this one. Will you send me your address as I'd like to send you something which I think will interest you. You can email me at gl.lawson@googlemail.com

Gemma x

Post a Comment